There are probably more definitions of the (engineering) manager’s role out there in the industry than there are stars in the galaxy. So how to understand what I should be accountable for?

Naturally, the first stop to understand that is your organization’s very own role descriptions. However, I noticed that all great leaders share a similar attitude towards whatever is happening around them, regardless of the company. They don’t go back to the documentation to double-check if solving that particular problem in front of them is their responsibility or someone else’s. Instead, they act as complete owners, like their team would be a small independent company working on a vision within outer context’s socioeconomic boundaries. And, quite often, even more than that!

No matter what your official title is, can you be that mini-CTO?

Immediate Team Circle

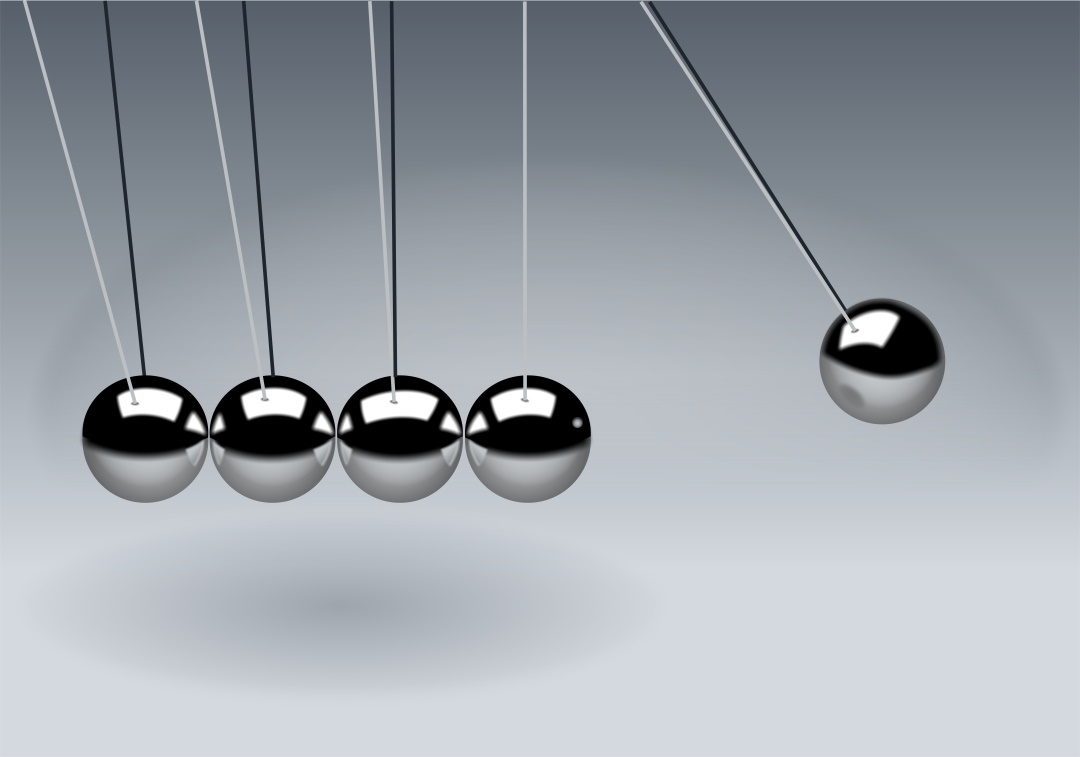

Let’s start with the obvious: you are fully responsible and accountable for your direct reports and your team’s performance. Everything, everything, what is going on inside the team, is your business, period. This includes individuals, their development, quality of outputs, technical debt, any conflicts, vision, you name it. The team, as a unit, is also entirely under this “immediate team” circle. Meaning you need to take ownership of how the team is perceived, what’s the team’s scope, how communications are handled, any aspects of the team development, and readiness for any next challenge that might be coming up.

Extended Team Circle

While being accountable for your team is not a surprise for anybody, the surface area of a leader’s impact is far from complete. The truth is that no team works in isolation, even if your team is the only one in the entire company. You always have other groups and/or individuals collaborating with your team and have a very real impact on your outputs. So here you go - if something is ultimately essential for your team’s success, you, a good leader, also have to own it.

That does not mean seeking a direct management line of everyone around your team (while could be an admirable career aspiration). Instead, owning a full cycle of communications, expectations, and feedback. Having some real influence on how things are done when it comes to your team <-> anyone contributing to your team’s success.

For example, you have a project to deliver. And as often happens, there are two dependencies another team has to finish before you can wrap up your work. Working on the extended circle means:

- Communicating with another team they are on your critical path

- Checking if their delivery plans match your needs, actively seek for adjustments if that’s not the case

- Following up on progress, are there any unforeseen problems down the road?

- Agreeing on hand-over, post-release, and long-term maintenance, e.g., who will be responsible for fixing a bug if it bubbled up inside the dependency right after the deployment?

To put this in simple terms: if somebody outside your team has a real difference in your team’s success, you want to be sure you did everything reasonably possible to influence it to go exactly as expected — no less.

Force Majeure Circle

The last circle, and the furthest away from the center of the universe your team, is what I only half-jokingly call “Force Majeure.” The concept explained in the “Extended Team Circle” part applies to everything you can’t control or influence. For example, someone got sick. Performance issues due to some family-related situation. StackOverflow down for 2 hours. Or some other horrible event we usually have no control over, but it’s life, so they do happen.

But if you can’t influence that, what am I talking about?

It’s about thinking through risks ahead of time and baking just the right amount of plasticity and flexibility in your team. Let’s take that first example of someone getting sick. On the one hand, how do you know about such things in advance at all? On the other hand, if you plan 100% of the team’s theoretically possible capacity for a mission-critical project during a regular covid season (I hope this statement ages well!), it’s simply short-sighted planning. If someone having performance issues due to some external events in their lives, did you make sure there are no knowledge areas in the team where the bus factor is exactly 1?

Suppose aliens land on the Earth tomorrow, and we’re all busy sharing inspirational TikTok videos for a couple of days. Are you sure this will make any dent in the expectations of your next project’s delivery date?

So you get the idea - regardless of what’s going on, is the team’s structure, skillset, attitude, and overall organizational level ready to absorb and move on, or would it break down?

As Andrew S. Grove wrote in his timeless classics “High Output Management”:

You need to try to do the impossible, to anticipate the unexpected.

Wow, But

Yes, that’s a lot to expect. But is it? We anticipate our Senior Engineers to identify unforeseen issues and design software to be reliable regardless of external factors. We already hope that if the search box microservice goes down, the entire e-shop is not just giving up: maybe it’s a bit inconvenient for a few moments, but you can finish your purchase.

In the same way, it’s ultimately reasonable to expect senior leaders to see and work on the issues not only right in front of them but entirely out of sight.

Photo by Pexels

Comments